IN BRIEF

There is a concerning rise in hate speech, xenophobic and homophobic attitudes in European countries, and other parts of the world as well. A reminder that hate isn’t a distant concept; it’s in our neighbourhoods, our schools, our feeds, and too often, it goes unchecked. But amid this worrying trend, there is another, quieter story unfolding. Through youth organisations and non-formal education, young people are challenging hate, not with anger, but with dialogue. They are learning to listen, to question, to connect—and in doing so, they are rising above division.

Hope against hate: why peace education must rise in Europe

There is a concerning rise in hate speech, xenophobic and homophobic attitudes in European countries, and other parts of the world as well. I see it in the news, in statistics and in my everyday environment, Gran Canaria, Spain. On my walk to work, I see the mural of Isabel Torres, deceased actress and LGBTQI+ leader, vandalised periodically, and in a nearby town, racist graffiti against migrants appeared on the walls of a reception centre for unaccompanied migrant minors last month. Expressions like these are sadly not isolated nor innocuous incidents. They do not only hurt the social and minority groups to which they are targeted but communities as a whole, challenging peaceful coexistence and the very foundational values of our societies. It’s a reminder that hate isn’t a distant concept; it’s in our neighbourhoods, our schools, our feeds, and too often, it goes unchecked.

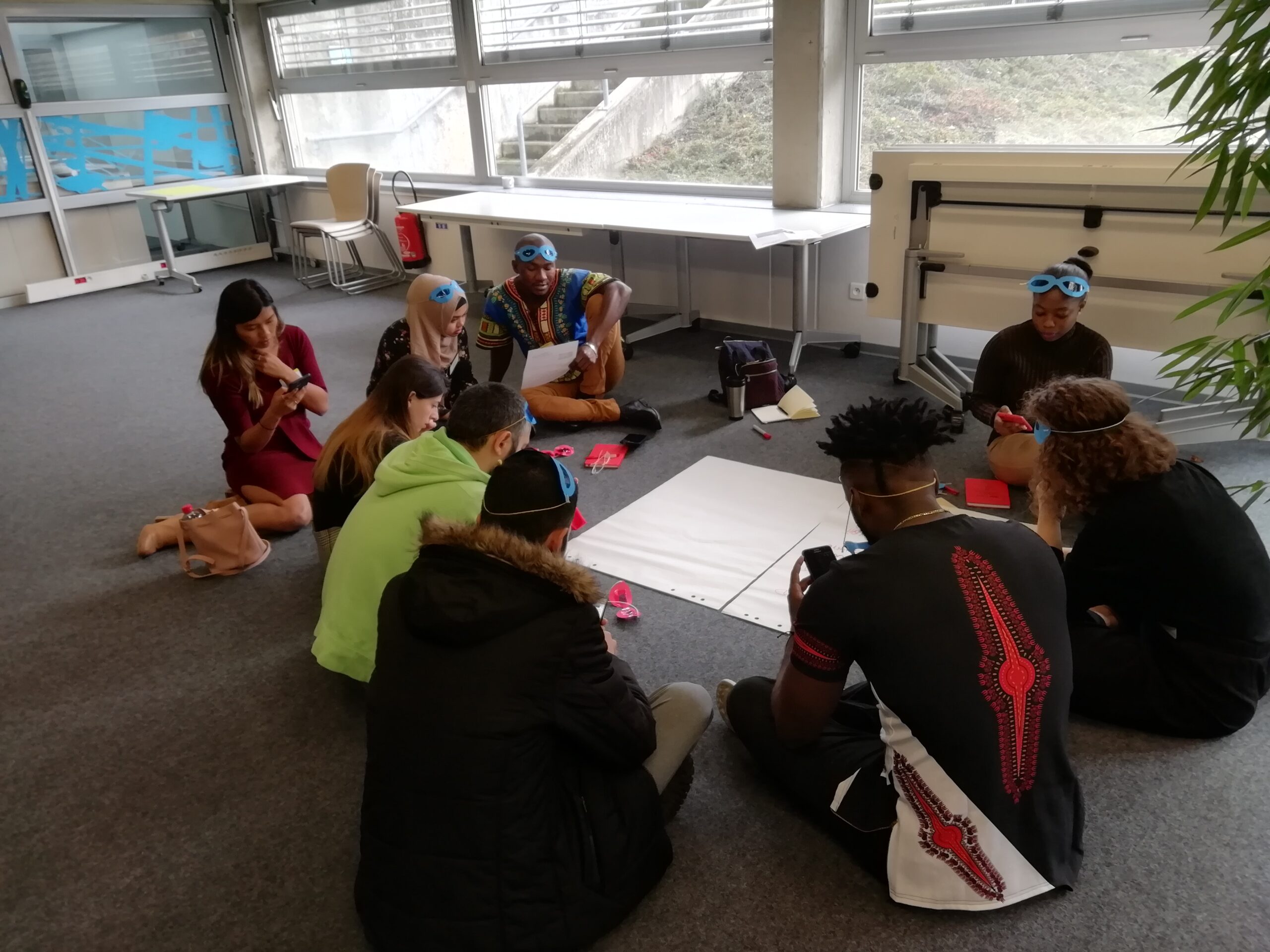

But amid this worrying trend, there is another, quieter story unfolding. One that rarely makes headlines, yet speaks to the heart of resilience and hope. As a peace educator working with youth organisations in non-formal education, I get to see how negative stereotypes, misinformation and fears fueling hate are addressed. Educators facilitate difficult but honest conversations and through them, develop critical thinking and media literacy skills. I am a privileged witness of stories of transformation in the context of youth work, and how bridges are built, despite challenges.Through youth organisations and non-formal education, young people are challenging hate, not with anger, but with dialogue. They are learning to listen, to question, to connect—and in doing so, they are rising above division.

The story of the No Hate Speech Youth Campaign

In the early 2010s, young activists in Europe noticed the growing toxicity of online spaces. Hate speech was spreading rapidly, targeting minorities with impunity.They brought this concern to the Joint Council on Youth of the Council of Europe, who proposed to start a Europe-wide campaign to address hate speech online in 2012.

Through art, humour, and storytelling, they didn’t just say “no” to hate—they offered something better: alternative narratives rooted in dignity, equality, and democracy.

Though the formal campaign ended in 2017, its spirit lives on. The No Hate Speech Network continues to empower young activists, reminding us that education and creativity can be powerful tools against dehumanisation.

Depolarisation Activism for Resilient Europe

In a time where educators are often accused of being “too political,” another initiative—Depolarisation Activism for a Resilient Europe—has emerged to help. This project equips educators with practical tools to talk about complex, sensitive issues like radicalisation, mental health, and polarisation. One of its key messages is simple, but profound: to reduce division, we must first learn to listen.

The project created various guides and tools for educators, building on insights from psychology, sociology, education, social and youth work and peace work. Currently, these tools are being shared and used by educators in other European countries, clearly, addressing a need. Earlier this year, the Irish Development Education Association hosted a training using the project’s Educator’s Guide to Depolarisation. One exercise stood out: instead of asking participants to defend their views, facilitators asked them to practise curiosity—to ask, not argue. The result? A room not of winners and losers, but of learners.

The “Trialog” creating brave space to talk about the Israel-Palestine conflict

Perhaps one of the most moving examples of peace education in action comes from Germany. Since 2020, Jouanna Hassoun, a Palestinian-German, and Shai Hoffmann, an Israeli-German, have been visiting schools together. In the wake of the October 7 attacks, their mission became even more urgent, and they developed a methodology known as “trialogues”. They visit schools together, and they engage young people in conversations about the conflict, antisemitism, islamophobia, and others, encouraging them to explore different perspectives, and also bring up their concerns and fears. They don’t shy away from difficult conversations, they lean into them. And by doing so, they create something rare: a “brave space” where young people can wrestle with complexity, listen to perspectives unlike their own, and grow.The fact that they work together and open up to answer questions in an honest manner despite their different backgrounds and opinions, has a strong impact on participants. They shared that in the great majority of cases, this experience is transformative for young people.

What now?

These stories are powerful—but they are not enough. Too many young people in Europe still lack access to peace education. Too often, youth work is underfunded, undervalued, or sidelined. And while grassroots efforts are inspiring, they cannot replace systemic support.. This is why it is of vital importance to strengthen and scale up peace education in the context of youth work to make it more accessible and inclusive. This should be done through enabling policies and financial commitments to non-formal education – on the one hand – and working on the many causes of hate speech with all relevant actors at the same time, on the other.

That’s why the recent Feasibility Study on Peace Education in Non-Formal Learning and Youth Work, commissioned by the Council of Europe, is so important. It makes a simple but urgent case: peace education should not be the exception. It should be the norm.

As illustrated in the examples above and as documented in studies, some like-minded young people, youth workers and educators have demonstrated their commitment to addressing hate speech and polarisation. Now it is time political actions speak louder than words and help us all rise above social divisions that could jeopardise the very foundations of our democratic systems.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Maya Angelou