This article is published as part of AP’s work in support of the Youth, Peace and Security agenda, as defined by UN Security Council Resolution 2250 (2015). To learn more about our work and read the other articles published, please click here.

From whichever side one observes them, Kosovo-Serbia relations seem like a never-ending story. While social and political clashes in recent years have hampered any attempted compromise, some small, but very valuable programmes seem to prove the opposite. This article will shed light on “Serbia and Kosovo: Intercultural Icebreakers,” a programme that uses arts to improve tensions between the two sides. This initiative has proven to be highly effective to foster positive perceptions and to contribute to reconciliation and peacebuilding.

Intercultural Icebreakers was established by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia to support the implementation of the Belgrade – Pristina agreement as well as to ensure quality media coverage of Kosovo-Serbia reconciliation efforts and the normalization processes. The project used a peacebuilding method called “contact work,” which created a space for youth from opposing sides to interact in person. The Committee chose up to 10 young artists or cultural workers from Serbia and up to 10 from Kosovo from an open call for applications. The selection process included questions about personal information, opinions, and reasons for interest.

Intercultural Icebreakers had two phases – a study tour and project development. In the first phase, two groups first gathered in Belgrade where they attended seminars, visited cultural sites and met with professionals working in the arts. After five days, the group traveled to Kosovo where they participated in the same activities in Pristina and Prizren. To ensure communication between the two national groups, each participant was paired with a participant of the opposite nationality for the duration of the study tour. At the end of the trip, each pair could decide to develop the final project together or separately. In the second phase of the programme, the participants either as a large group, pairs, or individually developed arts and cultural projects.

In 2017, the final project was an exhibition called “10 do 12, we’ve got time!” which included a mixture of photography, film, poetry among other artistic installations. The organizers of the exhibition explained the purpose of the project when they said the following:

“We, as members of the younger generations […] want to state that we have got the time to get to know each other better – and more importantly – to live and work in peace, never forgetting the past, but with a strong dedication to building a brighter future for all.”

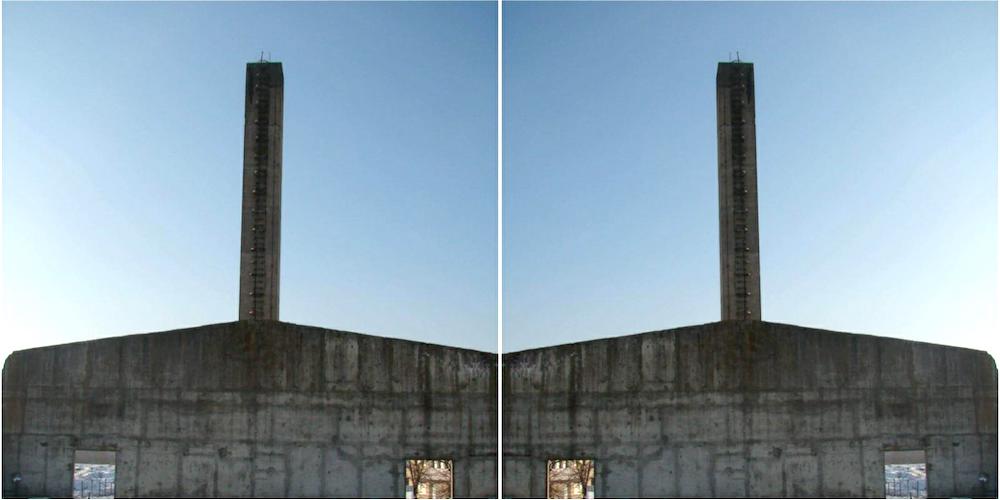

As one of the participants of the programme, I was involved in the “10 do 12, we’ve got time” show. My Kosovar partner and I used photography to show points of similarities in Kosovar and Serbian architecture. We called it “Common Sensing.”

We decided to find neutral things these two places have in common. We chose buildings. Through their differences, we wanted to emphasize their similarities in color, shape or symbol: a realistic picture of the current situation in Kosovo and Serbia, where through architectural images, the art and culture of the cities emerge. How far or close they are from each other, the common ones, or even the separate ones, may appear in an ideal way through these images. Buildings are part of visual perception, which, at the very end, is a conscious act of choice. We can choose what we want to see. We chose to see similarities between Kosovo and Serbia. To others we wanted to ask, what do you choose?

The programme itself was not just for personal cultural enrichment, but it also succeeded in promoting mutual understanding between the two parties. Results of the survey conducted two years after the exhibition showed that most of the participants had indeed changed their initial view about their neighbors. Even those whose view did not change entirely felt that their perspective “got better in quality, more detailed perception of what is going on, and how people actually live/think/act.” When asked how relevant these types of projects are, however, all of the participants answered “very important.” In addition, all of them would recommend participation in this project.

The positive and significant impact of the programme stems from the possibility for participants to break down stereotypes about “the other” in person. Some feedback by participants from both Kosovo and Serbia support this view:

“After I met so many great people from Belgrade with a big heart, and positive energy, who showed us that they are also human beings and think like we do. We had the same energy and need to work together in a group, to move forward, and create amazing things together.”

“I felt so welcome. I never had prejudices but there was a bit of feeling that I should remain cautious. But when I arrived everyone seemed and behaved so friendly with me, trying to welcome me in the best way. I was even offered a coffee by a complete stranger on the street and I have many memories that were made just in a few days. I wish I could have visited there even before.”

Furthermore, this programme opened new paths of communication between youth in Kosovo and Serbia, giving them the chance to create another narrative within their communities, and hence a different reality.

“First just in the entry of Belgrade while going to the hotel, we people from Kosovo saw a really bad word on a billboard in front of the Parliament Building, which didn’t make us feel so good and safe. And then we continued with the thought that our political relations aren’t so good, and they try to plant negative energy on the people from Belgrade. Then we arrived at the hotel, later we met with the group of the workshop, where the journey has just started. And good things were in the way… and I’m really glad I’ve met these people.”

On the question “has the perception of Belgrade changed after this project?”, the same participant said: “I showed to my family, friends, all about this workshop or journey as I call it, and explained to them in details everything, how we collaborate, what we did together, how we had so much fun together, learned so many things from each other, and how we created a good work in the end, an exhibition.”

Lastly and most importantly, this programme slowly but effectively creates a generation of different kinds of thinkers. With more open-minded solutions at their hands, these young people have an alternative of constructing better relationships with neighboring countries:

“I was telling the story of my trip to all the people asking me about where I’m from, which is almost everyone I happen to meet. They loved it, and could feel my excitement.”

“I continued to be involved in the project and expanded my circle of people and values. I would definitely use the practice of visiting both Belgrade and Pristina because for most of us it was the first time we visited those cities and that had a huge effect.”

Every year, another group of 20 young people participate in the programme. By 2030, these groups will hopefully have an even larger impact and there will be more creative proposals for enhancing cultural and political relations as well as more willingness to make positive changes:

“I confirmed the age-old saying that nothing is truly what it seems, which I would expand to the following: What you think you know is only a fragment of the whole picture.”

In conclusion, all of the above-mentioned factors are crucial steps for reconciliation. Art-based processes and common cultural experiences can be effective tools in raising awareness and rebuilding relationships. What they share is the importance of an emotional component, which is essential not just for reconciliation, but for the whole process of peacebuilding. Throughout the process of artistic creation and personal experience a link is formed between rational and emotional. This link is how we become aware of the ways we perceive and also of the possibility to change the meaning of that perception. Therefore, in the process of reconciliation, art can be helpful in terms of making both sides of the conflict aware of each other and, from there, creating common ground for mutual understanding.

Can we imagine a world where decision-makers propose artistic cooperation between parties in conflict to support their interstate relations? Can art and culture become essential tools for positive change in post-conflict societies? Maybe it is time to re-imagine international relations and start thinking about alternative, more creative solutions.

Vana Filipovski holds an MA in Peace Studies & MA in Cultural Policy and Management at the University of Belgrade. Driven by her belief that arts and culture can play a significant role in processes of reconciliation and peacebuilding, she was a part of various peace projects in Serbia and abroad. Vana is currently preparing to enroll in a PhD programme to analyze this topic more thoroughly.